i n the winter of 1935, a few months after the German government passed the anti-Jewish Nuremberg Laws, the Nazi family magazine Sonne ins Haus (“Sun in the Home”) sponsored a photographic competition to find “the perfect Aryan child.” On Jan. 24, 1935, the magazine published a front-page photograph of the winner, a beautiful 6-month-old baby girl named Hessy Levinsons. Nazi propaganda showcased the baby as “the perfect Aryan baby.” Unbeknownst to the judges, Hessy was Jewish.

Hessy had been born in Berlin on May 17, 1934, to Jewish parents Jacob and Pauline Levinsons. The couple, originally from Latvia, where they both had studied classical music, married before immigrating to Berlin in 1928. Both were singers: Jacob was a smooth-voiced baritone; Pauline had studied at the renowned Riga Conservatory in Latvia.

Jacob had accepted a position at a local opera house and taken the stage name of Yasha Lenssen to conceal his Jewish identity, since this was a time of intensifying antisemitism in Hitler’s Berlin. However, when the opera directors found out that Jacob’s family name was really Levinsons and he was Jewish, they canceled his contract.

Without money, and living in a cramped one-room flat, Pauline gave birth to Hessy. She was so beautiful that when she was 6 months old, her parents decided to have her picture taken. “My mother took me to a photographer,” Hessy recalled. “One of the best in Berlin. And he made a very beautiful picture.”

Hessy’s parents liked the portrait so much they had it framed and propped it up on the piano that Hessy’s father had given her mother as a present after Hessy was born. Her parents thought the picture would remain a private family photo. They were unaware that Hans Ballin, the well-known Berlin photographer who had taken it, had entered the picture in a photo contest of the Nazi magazine Sonne ins Haus.

When the woman who helped clean the apartment arrived, she delivered some surprising news. “You know,” she said, “I saw Hessy on a magazine cover in town.” Hessy’s mother said it could not be Hessy. “No, no, no,” the cleaner insisted, “it’s definitely Hessy. Just give me some money and I’ll get you the magazine.”

The photograph had been selected from an assortment of a hundred pictures of German babies taken by 10 well-known German photographers. The competition had been arranged by the Nazi propaganda department headed by Joseph Goebbels, to showcase the ideal beautiful German Aryan baby. The winning baby picture would appear on the cover of Sonne ins Haus.

Ballin put Hessy’s photograph along with nine others into an envelope and sent it to the office of the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. He knew full well that Hessy was Jewish. Even though the Nazis typically promoted blond hair and blue eyes as the ideal Aryan features, for whatever reason, the picture of the brown-haired and brown-eyed Hessy won.

Fearing that the Nazis would discover that their family was Jewish, Hessy’s mother informed Ballin. The photographer replied that he knew. He said he deliberately entered Hessy’s photograph into the contest because “I wanted to make the Nazis look foolish.” He explained that “I wanted to allow myself the pleasure of this jest. And you see I was right. Of all the babies, they picked this baby as the perfect Aryan.”

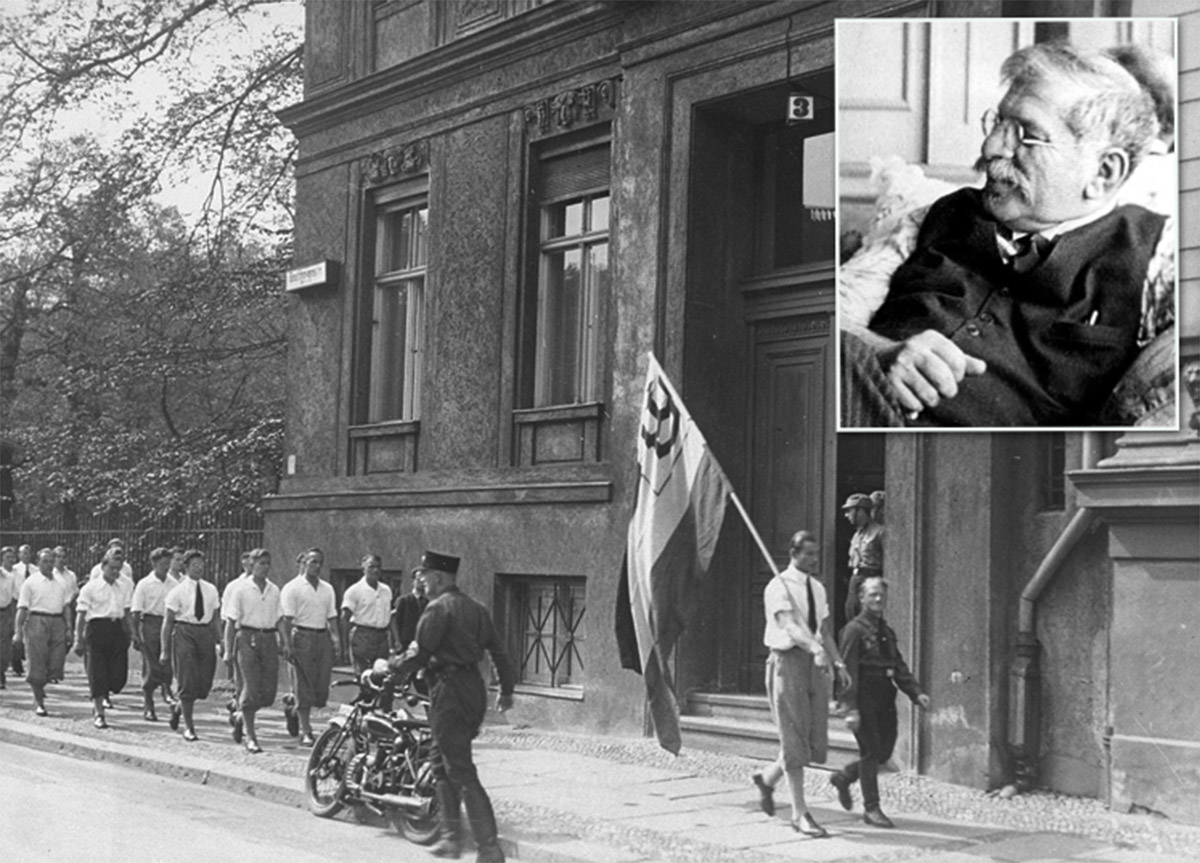

The magazine was one of the few publications that were allowed to circulate at the time. Edited by a friend of Nazi leader Hermann Goering, the magazine broadcast the virtues of Nazi Germany and the superiority of the Aryan race. Its pages brimmed with photos of men wearing swastikas.

The Levinsons were horrified when their daughter’s photograph appeared in its pages. Her face was plastered all over the streets, in storefront windows, and in newspapers and magazines. Hessy’s picture was later distributed on postcards throughout Germany and in the countries they occupied. Hessy’s aunt even found a card in Memel, Lithuania, with Hessy’s photo and the inscription in gold letters, “Best wishes for the birthday.”

Out of fear of Hessy getting recognized and maybe even killed, her parents hid her from the public eye. “I could no longer play in the park,” she recalls, “and I couldn’t go to the zoo, my favorite place.”

One close call occurred when a friend of the family had been visiting a German woman’s apartment and spotted Hessy’s photo framed on the wall. She accidentally blurted out, “But that is Hessy Levinsons.” The woman responded angrily, “What? Did you say the baby’s name is Levinsons?” The woman pulled the picture off the wall and pensively stared at it for a while, and then calmed down and said, “Oh, never mind. She is too cute. I’ll hang it back.”

Hessy’s parents were filled with trepidation at what had occurred, but in spite of their unease, they were also astonished at the absurdity of it all. “One time,” Hessy says, her aunt went to the store to buy a birthday card for her first birthday in May of 1935, only to find a card with Hessy’s baby picture on it. “My aunt didn’t say another word, but she bought the postcard which my parents carried with them throughout the years.”

Many years later, Hessy was asked what she would say today to the photographer who entered her picture in the contest. She responded that “I would tell him, good for you for having the courage.”

“I can laugh about it now,” she says. “But if the Nazis had known who I really was, I wouldn’t be alive.”

In 1938, Hessy’s father, Jacob, was briefly arrested by the SS on trumped-up tax charges. After this, he concluded that Germany was no longer safe for him and his family and determined to leave immediately. He took his family and moved to Latvia, his home country. After a short stay, they relocated to Paris.

At one point during their sojourn in Paris, Hessy developed an earache and her mother found a physician who would make a house call. The doctor who came was Jewish and he commented on what a cute child Hessy was. Pauline told him the story of Hessy’s baby photo. The doctor responded by pointing out that there were an increasing number of people in France who were influenced by Hitler’s propaganda. He told them that he had connections at a Paris newspaper, and believed this would be a great story to publicize and make the Nazis look foolish.

Pauline was agreeable, but Jacob said, “No way.” The doctor turned to him and said, “You know Mr. Levinsons, you have no reason to be fearful. You are not in Germany anymore.” The soon-to-be Nazi occupation of France proved the doctor wrong.

France fell to the German army in June 1940, and Hessy’s family was smuggled into the “zone libre” (free zone) in southern France. Her father struggled to obtain visas for the family to emigrate from France—they received a U.S. visa in 1941, but were unable to leave before the visa expired and could not obtain an extension.

Luckily, in 1942, the family acquired visas to enter Cuba. Hessy’s father then purchased train tickets to take them from Marseille to Lisbon, Portugal. In Lisbon, he bought boat tickets to sail to the Americas. As the family waited in Marseille, they discovered that Gerta, the young Jewish nurse the family had hired in Berlin and who had gone to Paris with them to take care of the children, was refused a visa to join her brother, who had already immigrated to Oregon.

Gerta remained in Paris. Hessy’s parents now faced a dilemma: Should they return to Paris or just leave Gerta there? Hessy’s father had no visa for Gerta and no pass for her to get back to Nice. But they feared that Gerta, as a young Jewish girl, would likely be killed. Hessy’s father then headed back to Nice, while the family waited for him in Marseille.

While on the train to Nice, Hessy’s father stayed in the dining car, believing it would protect him. He kept ordering food and wine until he was almost drunk and sick. When the train stopped for two hours at the checkpoint to enter the Vichy sector, the guards examined the passengers’ passes, but walked right through the dining car without disturbing the diners.

While in Nice, Hessy’s father had pawned his silver cigarette case and went back to the Cuban consul to offer him more money for another visa for Gerta. The consul said, “I already gave you four visas and am in enough trouble.” Hessy’s father told him that he would not leave until he gave him another visa, sat down, and waited. At the end of the day, the consul said, “I am going to close. Are you going to leave or should I call the police?”

Hessy’s father responded, “I’ll leave as soon as you give me a visa.” The consul looked at him and said, “You know, there is an old law in the books in Cuba that says a man can immigrate with all his possessions, including his slaves. Would you say this woman is your slave?” Hessy’s father said, “Of course. Absolutely. This woman is my slave.” The consul gave him one more Cuban visa.

Hessy spent much of her childhood in Cuba. In 1949, she and her family immigrated to the United States and settled in New York City.

There, Hessy Levinsons got married and became Hessy Levinsons Taft. But her father stayed behind in Havana to operate a business, which thrived until the advent of Fidel Castro, when it foundered. Hessy says that her father always said, “I have survived Hitler; I will survive Castro.” Hessy says “And he did, he did.”

Hessy studied chemistry at Julia Richman High School in New York City, and majored in chemistry at Barnard College, graduating in 1955. She worked in academia for a while until she left to raise a family, though she returned to professional life later and helped run the AP chemistry exam for the Educational Testing Service. After 30 years in the Educational Testing Service, Hessy returned to New York in 2000 to work as a chemistry professor at St. John’s University, where she studied water sustainability until she retired in 2016.

Although Hessy’s immediate family survived the Holocaust, most of her extended family in Latvia were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators. When she was asked how she felt about being a Jewish poster child in a Nazi propaganda magazine she said: “I feel a sense of revenge, good revenge.”